Book Review #1 - Atomic Habits

We both enjoy reading books, and often try to apply what we learn to our badminton and general life. We thought it would be a nice idea to share our thoughts on books that we read with you guys, and hopefully can share ways for you to apply the ideas to your life too. Our first book review is Atomic Habits by James Clear, which I (Jenny) recently read.

Who Should Read It?

Essentially anybody who wants to become more productive in their life and create positive lifelong changes rather than quick fixes.

✍️ Our Top 3 Quotes

1. It is your commitment to the process that will determine your progress.

2. Surround yourself with people who have the habits you want to have yourself. You’ll rise together.

3. Never miss twice. Missing once is an accident, missing twice is the start of a new habit.

Why Tiny Changes Make a Big Difference

Making a choice that is 1% better or 1% worse seems insignificant in the moment, but over the span of moments that make up a lifetime these choices determine the difference between who you are and who you could be. Success is the product of daily habits.

Making something a habit over the long-term means that you do it without even thinking, such as brushing your teeth every morning. The more we can make habits require no thinking, the more we can focus on other things.

Badminton example: working on creating the habit of your serving process will require a lot of thinking in the beginning. Once you make this into a habit, you can then focus more on your placement, opponent and 3rd shot.

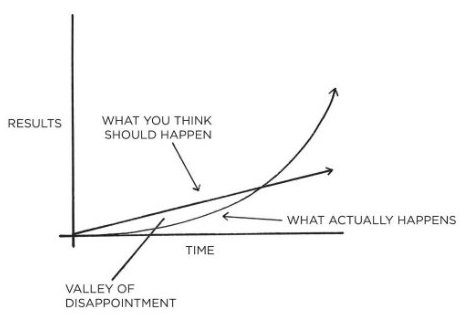

However, people (and we are all subject to this), don’t see results quick enough so they stop implementing these good habits. They then fall back into the old ways, and not improving the life that they envisioned that led to creating that habit in the first place. This is the “valley of disappointment”.

The “valley of disappointment” is why we should focus on the system or process, and not the goals or outcome.

Goals are good for setting a direction, but systems are best for making progress. Problems arise when you spend too much time thinking about your goals, and not enough time designing your system to achieve the goals. Ultimately, it is your commitment to the process that will determine your progress.

Badminton example: if you spend too much time dreaming of winning the Olympics, but only training 5 hours per week because you’re too lazy to do the other 25 hours, then your progress will never take you towards the goal of the Olympics.

To actually create habits, they need to become part of who you are (e.g. the goal is not to win a badminton match, the goal is to become a badminton player).

But what happens if you’re stuck in the identity of “I’m never going to be good enough to become a badminton player”? You need to change your identity by deciding the type of person you want to be – what do you want to stand for? What are your values? Who do you want to become?

If you want to become world number one in Mens Singles, ask yourself “what would Kento Momota or Viktor Axelsen do?” Would Viktor skip this training session because he is a little tired or wants to go to the cinema with his friends?

Everything you do, ask yourself “am I becoming the type of person I want to become?”

The most effective way to change your habits is to focus not on what you want to achieve, but on who you wish to become.

The book introduces 4 laws of creating a habit: cue (make it obvious), craving (make it attractive), response (make it easy) and reward (make it satisfying).

The 1st Law - Make It Obvious

Firstly, you need to look at your current habits. If you’ve done something 1000 times then you are less likely to know you’re doing it. We’ve come across this a lot in badminton – when you’ve played a shot with the ‘wrong’ technique 1000 times, you don’t realise anymore that it’s wrong. Changing your behaviour starts with awareness – you can’t change something that you don’t know is wrong!

One way to increase the chances of your desired habit occurring is to make it obvious. This can be done by designing your environment for the habit to take place.

For example, it’s easy to not go to the gym when your gym clothes are at the back of your wardrobe and you can’t see them. Creating obvious visual cues (e.g. moving your gym clothes in-front of your night-out clothes) will increase the chance of you going to the gym on Friday and Saturday.

Habits thrive under predictable circumstances. Make sure the best choice is the most obvious one.

To reduce bad habits, spend less time in tempting situations. This is because bad habits are “auto-catalytic”. For example, you feel lazy because you skip badminton training. Because you skipped badminton training, you feel lazy.

The 2nd Law - Make It Attractive

The goal is to make the habit irresistible (or a bad habit unattractive).

To make a habit attractive, we can use “temptation bundling”. This is where you pair an action of something you want to do with something you need to do. For example, if you want to watch Netflix but need to go to the gym to get stronger on-court then…. “after I have gone to the gym, I will watch Netflix for 5 hours” (probably a bit excessive).

Another way to make a habit attractive is to join a culture where your desired habit is the norm. For example, if you want to train more, join a badminton club that meets up 5 nights per week, rather than your current 1-2. If you have to change your habits in a positive way to fit in with the culture, then the change is attractive.

Surround yourself with people who have the habits you want to have yourself. You'll rise together.

Habits are attractive when we link them to positive feelings. We all need to have a mindset shift from “I have to” to “I get to”.

- I get to go to badminton training today.

- I get to travel the country or world playing badminton.

This simple word change highlights the benefits of the task at hand, rather than the negatives.

The 3rd Law - Make It Easy

It's easy to get bogged down trying to find the optimal plan for change: the fastest way to lose weight or the best program to build muscle. We're so focused on figuring out the best approach that we never get around to taking action.

“Figuring out” is called being in motion – planning, strategizing and learning. “Taking action” is producing the result. I am definitely a victim of doing a lot of planning, I am a very organised person.

However, I’m sure I’d be much more productive and achieve more of my goals if I got round to starting the action earlier. Planning and strategizing is still really important, but it will never get us to the result.

Why do we like the motion phase? Because we feel like we’re making progress and getting things done. In reality, we’re just preparing to get it done. Creating an on-court training plan to win a tournament in 8 weeks is good, but if you spend 4 weeks planning it then you won’t be able to take enough action to win the tournament!

If you want to master a habit, the key is to start with repetition, not perfection.

James says that to master a habit, repetition is the key to ‘encoding it’ in our brains. Most of us don’t want the habit, we want the outcome. For example, we don’t necessarily want to train our footwork for 2-3 hours EVERY week. We want the outcome of perfect footwork to help us move better round the court.

The more difficult the habit is, the more friction there is between you and the desired goal. This is why we should make our habits so easy that we’ll do 2 hours of footwork every week, even when we don’t feel like it.

Inversely, we should increase the friction associated with bad behaviours. When you know you should go to the gym at 6pm on a Friday rather than playing on the PlayStation, increase the friction (e.g. unplug your PlayStation and lay your gym clothes out by the door so you can’t miss them).

This little choice (deciding what to do at 6pm on a Friday) is a moment that can deliver an outsized impact. They stack up, setting the trajectory for how you spend the next chunk of time. For example:

- You choose to play the PlayStation, therefore feel lazy and order a pizza because you’re feeling lazy.

- You choose to go to the gym, and feel healthy and energised after the workout so make yourself a nutritious meal when you get home.

The Two-Minute Rule states that when you start a new habit, it should take less than 2 minutes to do.

This makes your habit really easy to start and usually, once you’ve started, it’s a lot easier to continue doing it.

The point is to master the habit of showing up. The truth is, a habit must be established before it can be improved.

Let’s be honest, creating the habit of doing a 1-hour footwork session per week seems quite daunting. Applying the two-minute rule, you simply go to the hall and say you’ll do just two minutes when you turn up.

If you do more than 2 minutes, great. If you don’t, you are still reinforcing the identity you want to build. Remember – it’s about the process, not the end goal. You should see the time you spend doing this increasing, and a habit is created.

The 4th Law - Make It Satisfying

A lot of things in life are within a delayed-return environment. This means that you can work on something for days, weeks or years before you see the intended payoff. For example, you can go to the gym today but might not lose weight for 6 months.

This is why bad habits are so prevalent. Usually, the consequences of bad habits are immediate (e.g. eating a bar of chocolate) and usually feels good, whereas the immediate consequences of good habits are unenjoyable (e.g. not eating the chocolate bar to lose weight) and the ultimate outcome is delayed (e.g. losing weight). The outcomes are misaligned.

The downside: when we are in that moment of decision, we usually choose instant gratification to feel full, pampered or entertained. We forget about ‘future me’ who dreams of being healthier, fitter, wealthier or happier. This highlights an important message:

Our preference for instant gratification reveals an important truth about success: because of how we are wired, most people will spend all day chasing quick hits of satisfaction. The road less traveled is the road of delayed gratification.

So, we must try and add some immediate pleasure to our ‘long-term habits’, and some immediate pain to any bad habits. Adding immediate pleasure can enable us to start a habit, then once it becomes automated our identity sustains it.

One way to keep our habits on track is to remember “don’t break the chain”. The rule:

Never miss twice. Missing once is an accident, missing twice is the start of a new habit.

To help not break the chain you can simply mark an ‘X’ next to each day you’ve achieved your habit. Doing this helps us to again, focus on the process rather than the end result.

One way to help us make bad habits unsatisfying is to make them painful in the moment. We can do this by creating a ‘habit contract’ – if you know you miss your footwork session every Tuesday evening at the hall, tell the badminton club receptionist to charge you double for the court time each time you miss it.

How To Go From Being Good To Great

Find a ‘game’ where the odds are in your favour:

Through trial-and-error. To not spend months doing trial-and-error, we should use the explore / exploit trade-off. Exploration takes place at the beginning of a new activity. After the initial exploration, move your focus to your the best solution but keep exploring occasionally!

If you are winning, exploit, exploit and exploit! If you’re losing, explore, explore, explore! Google famously asked their employees to spend 80% of their workweek doing their official job, and the other 20% on exploration. This ‘exploration’ led to the creation of Gmail.

Choose areas that are most satisfying to you. What feels like fun to me, but work to others? What makes me lose track of time? Where do I get greater returns than the average person? What comes naturally to me?

Until you work as hard as those you admire, don't explain away their success as luck.

The final chapter also looks at how to stay motivated. One method is to stay on the edge of your current abilities – not too hard and not too easy. The challenge should keep you engaged so that you can achieve flow state. This is ‘being in the zone’ – something we’ll definitely cover more of in the future. In short, scientists have found that to be ‘in the zone’ and in a state of flow, a task should be 4% beyond your current ability.

Improvement requires a delicate balance. You need to regularly search for challenges that push you to your edge while continuing to make enough progress to stay motivated.

James goes on to mention boredom – stating that it is the “greatest villain on the quest for self-improvement”. Successful people still get feelings of boredom; the difference between the successful people and unsuccessful is that they are willing to endure boredom for success. If you are only showing up or putting in the effort when it’s exciting or convenient, you won’t be consistent enough to achieve remarkable results.

For example, you can’t only put maximum effort in when you play matches in training, you need to focus just as much on breaking down your technique or practicing your footwork. Is it clear we don’t like footwork yet?!

An important note is the cost of habits: you become less sensitive to feedback due to the automation. A system of review and reflection is therefore necessary so that you don’t make excuses, create rationalisations, or become complacent.

💡 Reminder: Whenever you want to change your behaviour, remember to ask yourself: how can I make it obvious? How can I make it attractive? How can I make it easy? Can I make it satisfying?

We hope you enjoyed our first book review, and we will definitely be doing more in the future.